“As a journalism and history teacher at an independent school near Boston, I’m not too proud to admit that I use comic books in my classroom. When we cover World War II, my students analyze the inaugural March 1941 cover of Captain America by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, which shows super-soldier Steve Rogers deflecting an attack while knocking out Adolf Hitler. When I teach writing, my students analyze Kingdom Come, in which an aging Superman is distraught over a conflict that wipes out much of the Midwest. The pages come alive with lifelike artwork by Alex Ross, while writer Mark Waid exemplifies clarity and concision by making optimal use of each speech bubble.

I use comics in my classroom because stories like these inspired my own interest in history. As a junior in high school during the 1990s, I read the classic March 1963 issue of Tales of Suspense, which includes Iron Man’s first appearance. In this story, the Viet Cong capture wealthy industrialist Tony Stark. To escape, Stark cobbles together his first primitive Iron Man suit. As a 17-year-old, I knew very little about the Vietnam War and what role America had played. The comics piqued my interest, and I went on to read several history books on the conflict. Weeks later, fate smiled upon me when my history teacher assigned a research paper on the Vietnam War.

So I was enthusiastic when comic-book writer Josh Elder invited me to present on one of his panels at the world-famous San Diego Comic-Con this summer. Outside Hall H, the biggest theatre at Comic-Con, over 130,000 fans waited in line for popular panels, like a Q&A with the cast from Avengers: Age of Ultron. Many were dressed as their favorite villains or caped crusaders, eager to celebrate their love of not just comic books (an increasingly small part of the convention), but also anything related to pop culture and science fiction: Panels related to Game of Thrones, The Walking Dead, and Frank Miller’s Sin City: A Dame to Kill For, were all big draws.

In smaller rooms, away from screaming crowds and the mainstream media, panels like “Creating Comic Books with the iPad,” “Popular Media in the Elementary Classroom,” and “Calling All Heroes! Comics and the Crisis of Higher Education” certainly didn’t generate as much excitement. But making my way to as many of those panels as I could—more often than not in busy rooms, a few with standing room only—made one thing very apparent: More educators are paying closer attention to comics in the classroom.

I realized as much last year when I first connected with Elder, a talented writer behind several titles for DC Comics, including Scribblenauts Unmasked and Adventures of Superman #10. Elder is the founder of a non-profit called Reading With Pictures (RWP), which, according to its website, aims to unite “the finest creative talents in the comics industry with the nation’s leading experts in visual literacy to create a game-changing tool for the classroom and beyond.”

Elder says his cause is both professional and personal. As the child of a single parent, he had to wait in line for government-issued cheese. He struggled at home, but in school teachers encouraged his love of comics, which played a large role in his success in the classroom (he went on to become a National Merit Scholar), at DC Comics, RWP, and beyond. “Comics made reading easy and fun,” he told me. “Once that happens, learning everything else becomes easy and becomes fun, too.”

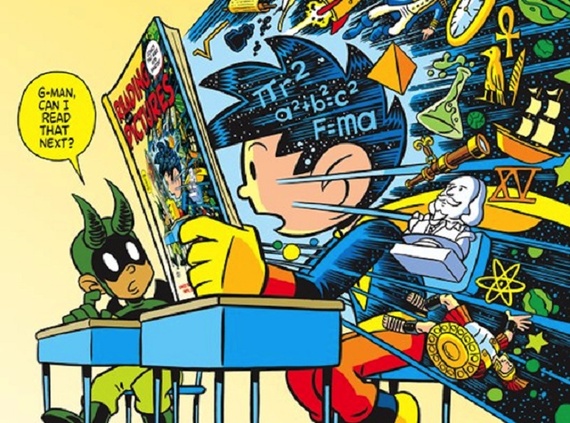

Last month, the organization released Reading With Pictures: Comics That Make Kids Smarter, an anthology featuring 180 pages of original content by top industry talents, including George Washington: Action President by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey, Doctor Sputnik: Man of Science by Roger Langridge, and The Power of Print by Katie Cook. Each story is aligned with Common Core Standards to justify classroom use. A 150-page teacher’s guide, with a lesson plan for each comic, is available for free download at the publisher’s website.

At Comic-Con, I spoke with Tracy Edmunds, RWP’s curriculum manager, who played a key role in crafting content and overseeing production. A former elementary school teacher, Edmunds has been working in educational publishing and curriculum development for over 20 years.

“All of my years of doing this have shown me that we need new tools, and comics bring a one-two punch with images and text working together,” she told me. Still, the idea of using comics as an educational tool is foreign to many teachers. “In creating this book and teacher’s guide,” explained Edmunds, “we wanted to give a reason for teachers to use comics, and the research and rationale behind their effectiveness.”

The study guide, which lays out its case in illustrated panels and in comic sans text, points out that comic strips as we know them were invented by an educator—a former Bronx high school principal named Maxwell C. Gaines. By the 1940s, though, there was a public backlash; a 1942 article in the journal Elementary Education Review warned of “The Plague of Comics” polluting young minds and distracting them from serious schoolwork. The study guide argues that this was a mistake. Comic books not only awaken an early love of reading but also help children grasp abstract concepts. What’s more, graphic novels are considered works of literature in their own right: Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust story Maus won the Pulitzer Prize, while David Small’s memoir Stitches was a finalist for National Book Award.

“It always strikes me as supremely odd that high culture venerates the written word on the one hand, and the fine visual arts on the other,” says Jonathan Hennessey, the author of The United States Constitution: A Graphic Adaptation. “Yet somehow putting the two together is dismissed as juvenilia. Why is that? Why can’t these forms of art go together like music and dance?”

At one Comic-Con panel, where he was a co-presenter, Hennessey projected a page about a Neolithic civilization. “If you look at the image, imagine how much text would be required to establish what you see here,” he pointed out. “The human eye processes images something like 60,000 times faster than it processes text. This isn’t to say that text has no place, but it’s saying that images are very powerful, and if we use them, they could be powerful teaching tools.”

I’ve been assigning Hennessey’s book since its release in 2008; his accessible storytelling, combined with Aaron McConnell’s eye-catching art, do more to engage my history and government students than any other material I’ve found. As Elder points out, this is one of the greatest advantages to using comics in the classroom: “The biggest challenge is getting students to pay attention in the first place. Comics are a way to do that.”

In April, at the Chicago Comic & Entertainment Expo, I met Jim McClain, a 27-year career educator. About a decade ago, McClain wanted to try something new. “Instead of graphing butterflies on the coordinate plane, we graphed Superman’s pentagonal insignia while listening to recordings of his old-time radio show,” he said. Students loved it, and they grew more engrossed in the material. That enticed McClain to take the next step. “Since I never thought in a million years that DC or Marvel would let me use their characters for such a book, I decided to make my own characters,” he said.

Last year, McClain released Solution Squad #1, featuring impressive artwork by his niece Rose McClain. Each character in the book possesses a math-based superpower: La Calculadora, the team leader, has an eidetic memory and is able to perform complex mental calculations instantly. Abscissa runs at hyper-speed along the x-axis, while her twin brother Ordinate flies to great heights and dives to great depths along the y-axis.

Solution Squad #1 also appears in Comics That Makes Kids Smarter, and the free digital download contains an accompanying lesson plan by Edmunds and McClain: “Caught in a deathtrap in which the only means of escape is solving a prime-number puzzle, the team creates a list of prime numbers using a prime number sieve to crack the alphanumeric code and catch their archenemy, The Poser. Students will read and discuss part of the comic as a group and solve the encoded message alongside the heroes.”

McClain won a 2014 Lilly Endowment Teacher Creativity Fellowship to make a new digital version of his comic book, which he plans to premiere at New York Comic-Con in October.

Veteran comic book artist Nick Dragotta has also found a captivating way to teach science. His Howtoons use comic book illustrations and storytelling to show kids how to engineer fun things—like a marshmallow shooter or a rolling paper plate. “When the kids are reading a story, hopefully they don’t even know they’re learning,” he said, noting that Howtoons reinforces the growing “STEAM” movement by promoting science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics. Dragotta told me that reading the comics isn’t the only goal. “We also encourage kids to create their own Howtoons, and with that comes critical thinking. Just the act of doing a comic book instills critical thinking, including how to sequence things, how to establish things.”

None of this is to suggest that comics should replace textbooks and other traditional classroom materials. As James Bucky Carter, author of Building Literacy Connections with Graphic Novels and assistant professor of English at the University of Texas at El Paso, recently told me, he encourages educators to use comics as a helpful supplement: “Think about the big themes that you are exploring in your classroom and then see if you can’t find comics and graphic novels that fit those themes. You don’t necessarily have to feel like you’re reshuffling your curriculum; you’re just looking for material that will help your students address those things or answer those big questions that you’re posing to them.”

It’s an approach that has worked well for me, and I look forward to watching many more of my colleagues join in the adventure—superhero costumes optional.”

Source: TheAtlantic